Knowledge HUB

Beacuse we belive that sharing the knowledge is the best way to innovate

Audio Pricing Models – Part 1

Regardless of the product and its features being offered, product teams have a lot to consider when choosing a pricing model. I believe the primary consideration that any product manager, UX designer, and founders need to consider first is the following — how can they bring value to a customer?

Introduction

When digital technology entered the audio production space in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, it became clear that a new era of business was beginning. While the quality of these early digital products was not as advanced as what we see in 2026, an important trend was emerging. The barrier to entry in audio production dropped significantly, making the process far more affordable. Whether individuals were learning to record music in their bedrooms using a laptop or established professionals were working in commercial studios, accessibility quickly became a central topic of discussion.

Traditionally, recording and producing music required renting a professional studio and hiring an engineer, both at a high cost. In addition, the extensive equipment needed to meet industry standards further increased the expense of maintaining such spaces. Over time, however, software and hardware companies developed tools that gave creatives greater control over the recording process. Small, portable audio interfaces—such as the Focusrite Scarlett—entered the market, allowing users to record directly to their computers through digital audio workstations (DAWs). Even with just these tools, creatives were empowered to take the recording process into their own hands.

Fig. 1 – Focusrite Scarlett USB Audio Interface. With one microphone input, one instrument/line input, stereo monitor outputs, and a ¼ headphone output, anyone could make records at a fraction of the traditional cost.

As more people began creating music in this manner, it became increasingly clear that software developers and hardware manufacturers needed to adapt to the digital landscape. Accessibility became the new standard, and creatives were willing to pay for these tools—especially in contrast to the high costs of traditional studio rentals. This shift in the market required companies to rethink their pricing models to better align with changing consumer spending behaviors. Before examining the various pricing strategies and their implications, it is helpful to first understand the types of products that evolved during this period, as well as the benefits they introduced.

Digital Demands New Models

Two major areas reshaped by digital technology were hardware and software. Traditional analog tape recording methods gradually gave way to computer-based platforms. Without diving too deeply into every advantage and drawback of this shift—some of which deserve their own discussion—the impact on affordability is impossible to ignore. Computers and digital recording platforms cost far less than analog tape machines and large-format consoles, and the tools needed to record into these systems became cheaper as well.

Hardware

Unless a user required 16 or more analog inputs and outputs—typically found in professional studios—most songwriters were perfectly fine working with just one or two. For someone recording at home with a vocal, a guitar, or keyboards, this was just enough to complete their work. Early audio interfaces like the Focusrite Scarlett or the Avid Mbox offered this functionality for just a few hundred dollars, while a recording console with comparable input and output capabilities still cost thousands. When maintenance expenses were factored in, it became clear that traditional pricing models no longer aligned with this new era of accessibility.

There was also a major shift in the storage medium—from analog tape to computer-based storage. Tape was difficult to transfer, fragile to maintain, and physically cumbersome, while hard drives were smaller, easier to manufacture, and increasingly affordable over time. Digital storage also offered a major advantage: it did not suffer from the same physical degradation as tape. If analog recordings were not stored or handled properly, their quality could diminish over time. After investing countless hours creating music, the risk of losing fidelity due to mishandled tape was a frustrating and costly reality.

Software

Arguably the largest shift was the introduction of the DAW and VST-based plugins. The DAW quickly became the standard for the entire recording platform. For a one time fee (later we will discuss other pricing models), the recording platform could be purchased with a set of advanced tools and features. The only thing for the most part that could affect its performance was the computer itself it was being hosted on. Needless to say, the cost of computers were significantly cheaper than a console or reoccurring tape purchases.

One of the biggest changes, and advantages, was plugin emulations. Instead of purchasing an outboard compressor for thousands of dollars, for example, one can spend even $100 for a digital emulation of the physical model. Even better, you could use the plugin in multiple instances at the same time. This alone was a huge advantage that was never achievable before. Otherwise you would need ‘infinite’ physical pieces of gear to recreate this ability (I don’t think I need to explain what that could cost…).

Fig. 2 – Waves CLA-76 Compressor. Emulated from Chris Lorde-Alge’s personal 1176 FET-Compressor.

Up To Speed: Current Pricing Models

Fast-forward to 2026, the barrier for entry into music production is more affordable than ever, and saturated with companies providing accessible tools. But from a developer or product manager’s perspective, not all forms of payment and financing are treated equally. Just because an audio company/startup would benefit from one pricing model, doesn’t mean it would benefit the end customer. And if the customer were to perceive the cost of the product as negative, then no payment will cross into the organization’s bank. Then no one wins.

Now that we have a historical perspective of the products we use today, let’s look into the different kinds of pricing models that organizations should consider when going to market.

Perpetual Model: One & Done

Simply put, you pay a one-time fee and own the product indefinitely. In software, this model has been a standard for quite some time. Many companies like Waves, FabFilter, iZotope and more have used this structure, some even charging another one-time fee for newer upgrades (i.e. V1 to V2). For hardware, this has also been the standard (with the occasional monthly installment plan).

From the perspective of the customer, owning the product upfront is great in that you never have to keep paying to use it. No recurring payments let customers feel at ease, even if the one-time payment could be high. So while a company can retrieve a higher revenue stream with a single transaction, this also can have a negative affect for growth too. Assuming purchases are not consistent, this model makes it very hard to accurately forecast sales. And even if sales are consistent, if software is the product which could also have paid upgrades, customers may hold off on the upgrade for reasons such as added costs and compatibility requirements (the lack of). This may be able to bring in a large sum of revenue into the company, but it can quickly slow down due to the reasons mentioned above.

Another consideration is when a large update is released. Say from version five to six, there could be a plethora of new and useful features that justify an upgrade cost. Especially with regards to operating system (OS) compatibility, a cost would justify the company to charge a customer. A lot of time, money, and resources go into building new updates that aren’t just bug fixes. Customers in this case either pay to upgrade, or wait until their needs are either met or they update their operating system (a very common reason why customers wait to upgrade, for system compatibility).

Subscriptions: Small Costs, Recurring Billing

A model that exists in a multitude of industries, subscription models have become extremely popular in audio. It’s quite compelling, for example, to pay anywhere from ten to twenty dollars per month to gain access to dozens if not hundreds of plugins for your disposal. Companies like Splice, Waves, Avid, and more offer different tiers for various price points. Generally speaking, the higher the monthly fee, the more features you gain.

Even if you can gain a whole library of plugins that can be worth hundreds if not thousands of dollars, you don’t actually own the product. A lot of music producers and engineers alike treat their plugins like an artist does with their instruments; there is an emotional attachment to owning a product. Therefore, there is a built in risk of isolating this segment of customers who have this emotional attachment to their tools. So unless you only plan to subscribe for a few years at most, the long-term costs can get quite expensive. Plus, if you only use a portion of the included products, you could be paying extra for no added benefit. But of course, the enticing factor is that a customer doesn’t have to pay a large sum of money upfront.

And for people who just need the product for say a few months, this option may be beneficial; just pay for the time you need, and then stop. Instead of paying a large one-time fee for a product you only need for a set time, just pay for the time needed.

Now from the perspective of the company, this could really benefit overall growth. By having customers pay a consistent rate over a span of given time, it becomes significantly easier to have predictable recurring revenue (PRR). Budgeting and forecasting become much more straightforward, allowing for a more steady growth potential.

A big risk with this model is that the recurring funnel could fall quickly if mismanaged. Say if the subscription price was decided to increase a few dollars a month, without adding more value to the customer, they may decide to cancel their plan if they cannot justify the cost. Churn rates would spike exponentially, making it extremely hard to regain customers’ trust for gaining their business back. So regardless of your product’s value, this is a balance that should be regularly analyzed.

Fig. 3 – Slate Digital’s Virtual Mix Rack, included in their All Access Pass. Their subscription plan includes new products when made available, for no additional charge.

Rent-to-Own: Installments

Similar to payment installments, customers can pay a recurring value over a given period of time. And once payment has reached the threshold, they then own the product. This has become a very attractive model in the software side of the industry over the past several years. Simply, a customer can eventually own the product while paying in small batches to use it. And the key factor; if they stop paying in the middle of their plan, they can pick back up where they left off.

Yes, this does mean they would lose access to use the product at that moment. But they wouldn’t lose their payment history. Unlike subscriptions that require never-ending payment (unless they stop, which still means no ownership), rent-to-own means they can eventually stop paying and still claim lifetime access.

Splice for example have become a great outlet for this model, by allowing third party developers to sell their products via the platform. In this case, Splice becomes a reseller, so to speak, and turns into a central hub for customers to own (eventually) other great products. While Splice may have to take a cut of the revenue, this can become great exposure for developers because of the already built-in user base. If companies want to grow quickly, this is a model that could benefit especially in the short term.

Predicting Future Models (with Existing Patterns)

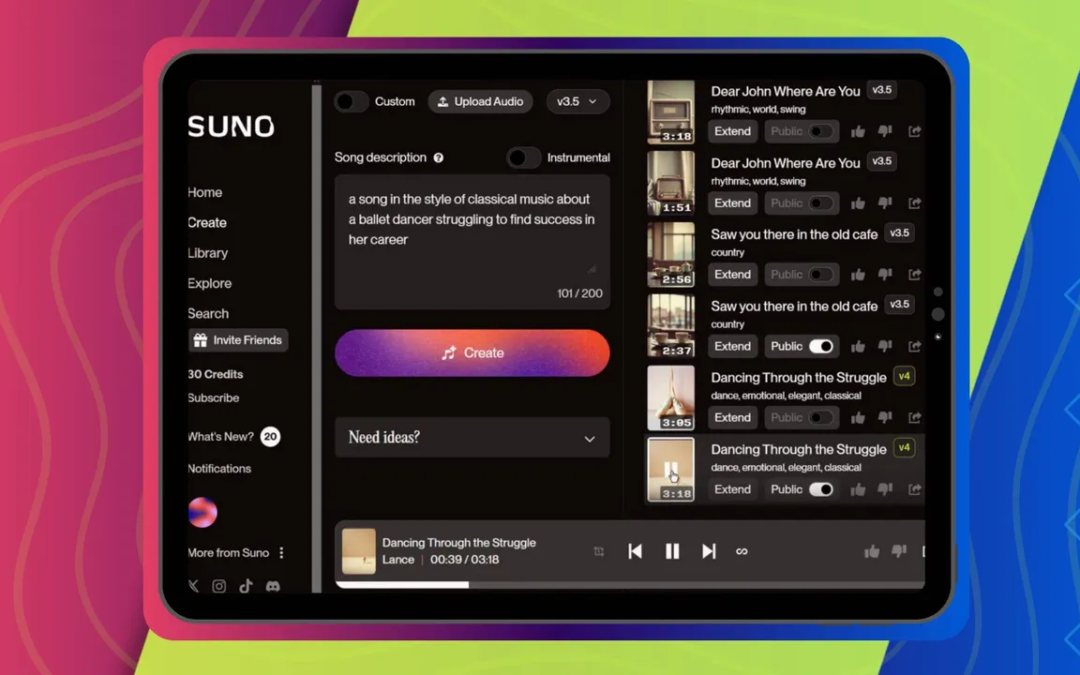

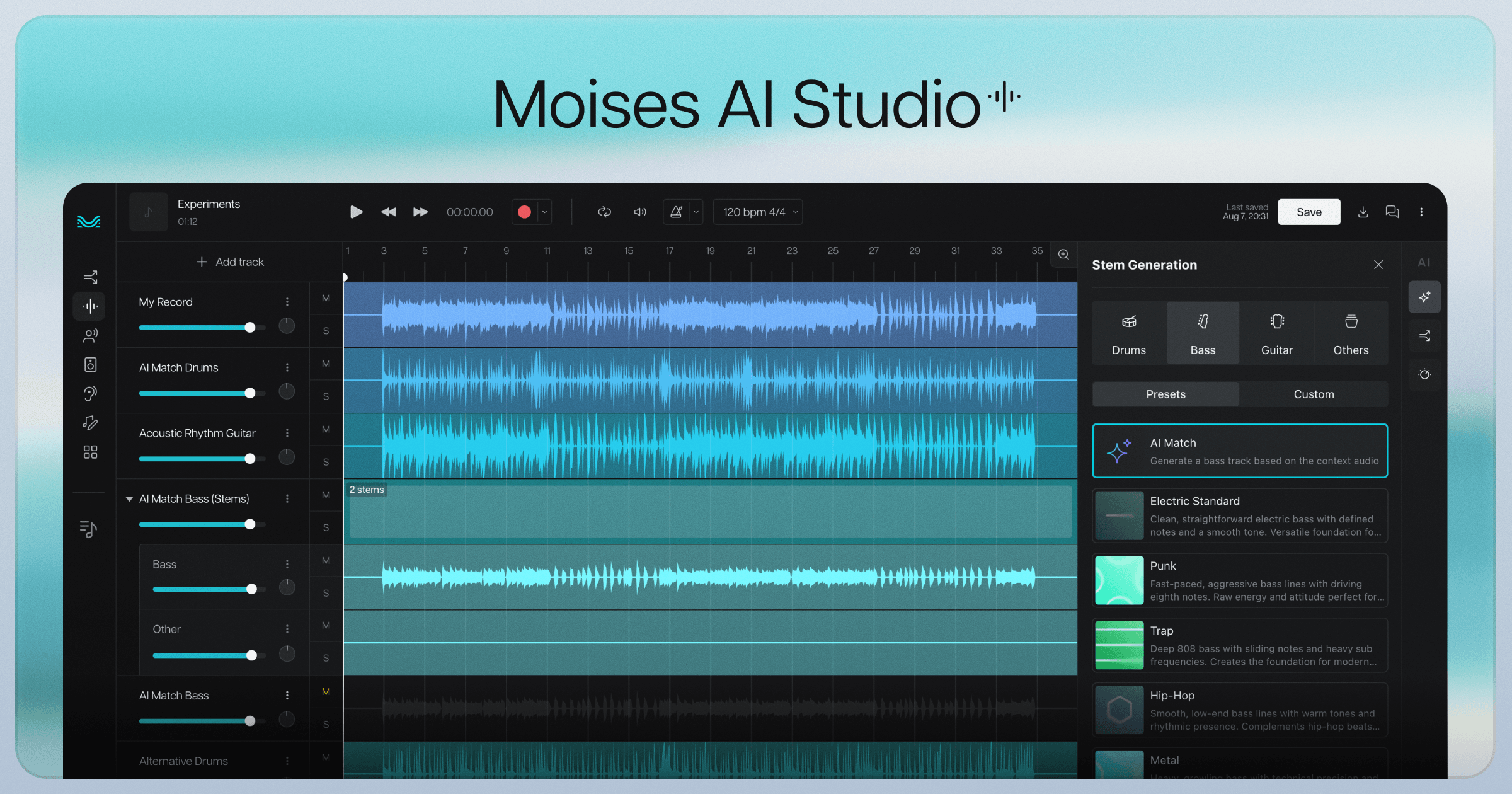

Even now with the introduction of artificial intelligence in audio products, new practices are being developed and adopted as we speak. A model typically found in the mobile “freemium” category, is the ability to pay for credits. Depending on the product, one can purchase a specific amount of credits that are redeemable to acquire samples, outputs, and more.

Splice have already had this model for some time, but even newer organizations like Moises AI provide users with a set amount of credits that can measure how much content is able to be generated in a given time period (typically a month in most cases). In this example, one credit equals 30 seconds of generated audio. For their free tier, Moises AI provides a user with 60 credits a month, while the premium and pro tiers give 200 and unlimited credits respectively. To make things more interesting, credits expire at the end of the month – no rollovers apply.

Now that we have entered the AI stage of music technology, it seems relatively clear that the hybrid subscription/credit system is here to stay. While the pricing model is something we have seen with traditional products like VST emulations and instruments, the focus is now on generated outputs. Whether the product in question can generate audio with a simple prompt, or assist in operational tasks, this model is centered around redeeming. Specifically speaking, redeeming is similar to a token system where a customer chooses how they want to spend their earned currency.

It will be interesting to see how consumers of AI-based products value a system like this, and if it makes sense for their workflows and needs for creating music. Will customers need more or less credits than they pay for? Or will they get tired of feeling restricted with a set amount of outputs that can be created? Only time will tell how creators – the customers – adapt with advancing technology.

Fig. 4 – Moises AI Studio

What Does This Mean for Product Teams?

Regardless of the product and its features being offered, product teams have a lot to consider when choosing a pricing model. I believe the primary consideration that any product manager, UX designer, and founders need to consider first is the following — how can they bring value to a customer?

The number of features is great and all, but that doesn’t automatically mean that customer value is being met. It’s extremely important that as a product manager, owner, etc, we test our hypothesis to gain valuable information. What good would creating a product for months and years be if customers don’t like the outcome? And testing pricing models should be equally considered in this. Even if product teams have tested and confirmed their overall product goals and theories, that won’t matter until pricing models show what revenue and margins will look like.

As mentioned earlier, pricing doesn’t only consider attributes like cost to make and intended return on investment (ROI), customer support and technical development all go into play when finding out reasonable and fair prices for products.

Being that this is part one of a bigger discussion, the next article will dive into the more specifics of how product teams determine the cost of their products. Careful considerations must be made to ensure that a company is actually making money, while still providing great quality and happiness to their customers.

Related articles